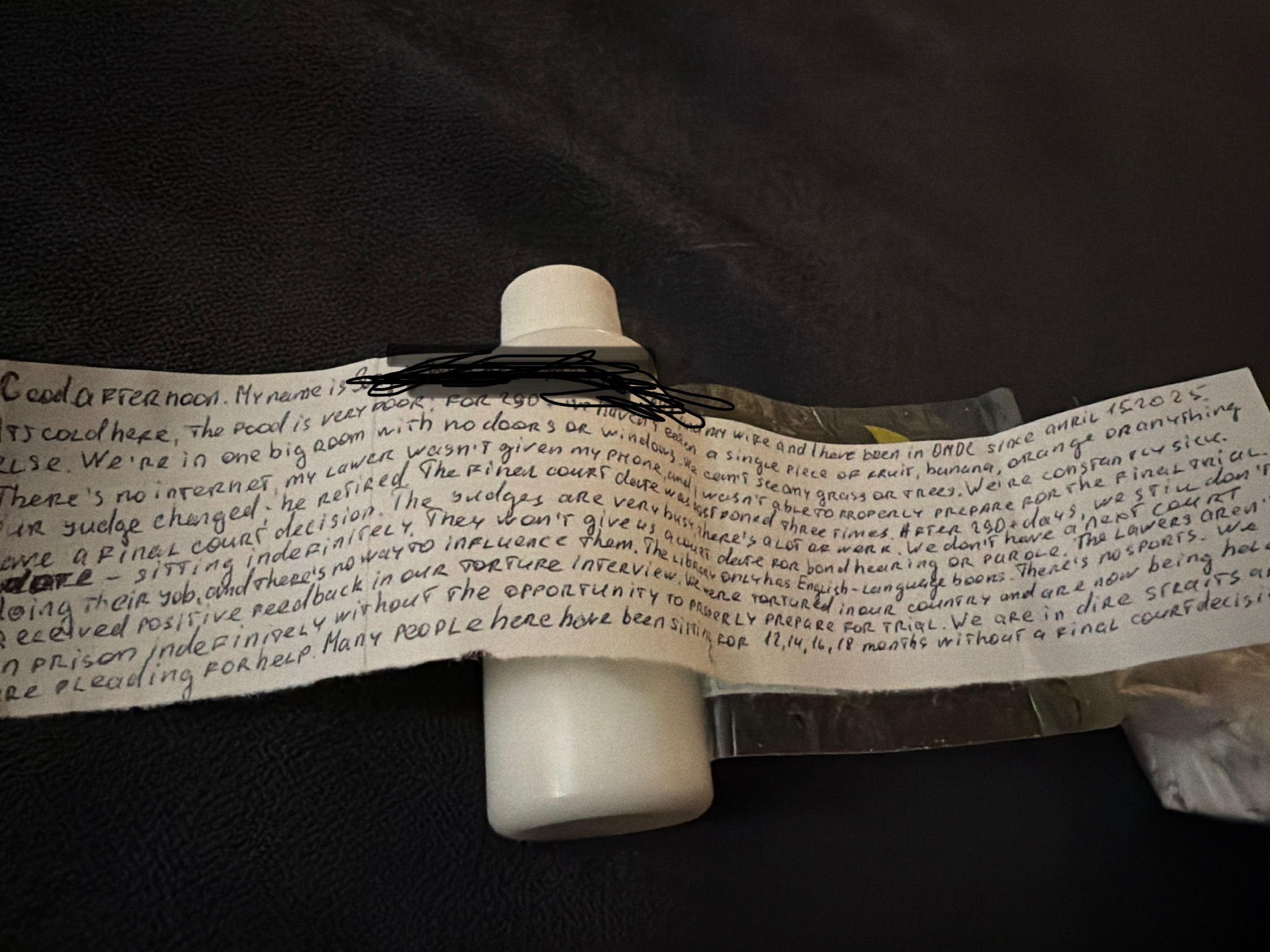

“Good afternoon. My name is [redacted] and my wife and I have been at OMDC since April 15 2025,” reads a handwritten note, wrapped around a lotion bottle that was thrown by a man held captive inside the Otay Mesa Detention Center (OMDC) on Sunday.

“It’s cold here all the time and the food is poor,” the missive continues. “For 280 days we haven’t eaten a single piece of fruit, banana, apple, orange, or anything fresh. We are all in one big room with no doors or windows. We can’t see any grass or trees. We are all constantly sick.”

The bottle needed to be tossed with enough strength to make it across a cement wall, two barbed wire fences each around twelve-feet high and separated by about five feet of gravel, and ten additional feet of road. All to make it into the hands of attendees of a weekly vigil held outside of the OMDC.

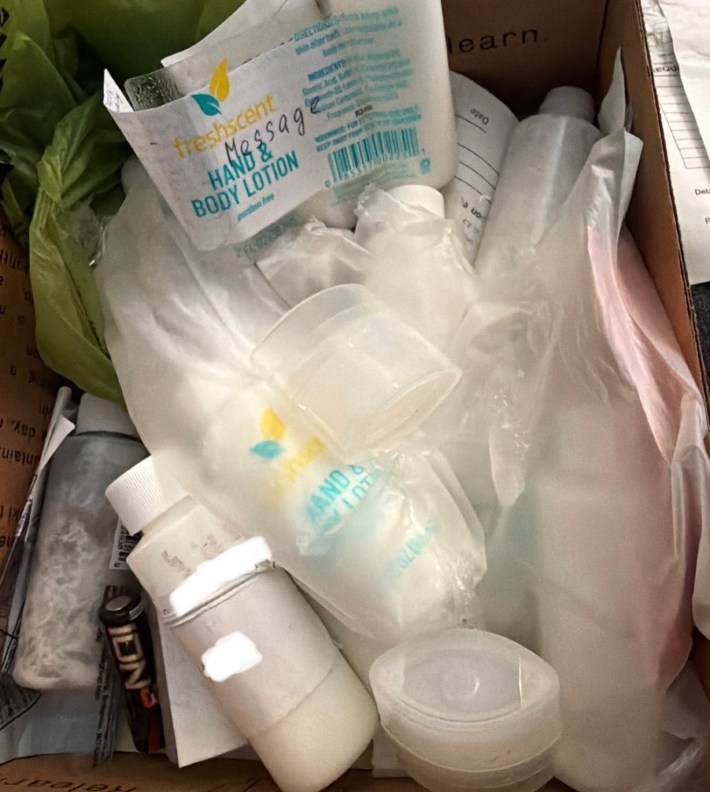

Two lotion bottles with the same note were tossed over from the detention center that day—organizers say that the captive was that desperate to get their story out.

As soon as organizers saw the bottles flying through the air, they rushed to grab them. It was a race between the vigil attendees and the CoreCivic security truck operated by detention facility staff. The vigil attendees won this time, securing the bottles and the precious, uncensored information inside.

About 150 people were gathered there that day. San Diegans have been assembling like this, outside of the privately-run federal immigration detention center, since November 2. That’s when San Diego Bike Brigade, a group that began patrolling local schools on their bikes to protect children from federal immigration activity, hosted its first vigil, now a weekly occurrence. What started then as a group of ten people is now growing each time they gather.

Otay Mesa Detention Center on Sunday, where organizers communicate with captives. Photo by Aisha Wallace-Palomares for L.A. TACO.

The weekly vigil is currently supported by a coalition of seven organizations, including the San Diego Bike Brigade, called the Otay Mesa Detention Collective. These include Borderlands for Equity, San Diego Families for Justice, San Diego Showing Up for Racial Justice, 50501 San Diego, and SD Activist.

The vigil began with the intention of bringing “awareness,” “hope,” and “solidarity” to the detainees, according to Jeane Wong, founder of San Diego Bike Brigade.

Organizers commonly refer to the detainees inside of the center as “hostages.” Wong says this is because the people held captive inside these facilities were taken from their communities, disappeared for days, and placed in “punitive camps with limited to no legal representation.”

They have collected 14 lotion bottles, two deodorant bottles, and one AA Battery that detainees have thrown over the fences with notes attached to them. These items have included a total of 102 names and A-Numbers. Organizers also collect countries of origin.

A-Numbers are seven, eight, or nine digit numbers assigned by the Department of Homeland Security to people who are not U.S. Citizens, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Organizers use this information to add anywhere from $20 to $45 to detainee accounts on Connect Network, an app that collects funds for detainees’ commissary. They add $10 to $20 to accounts on the GTL GettingOut App, which is used for phone calls.

L.A. TACO reviewed transactions provided by the Otay Mesa Detention Collective. There are four organizers who have become experts in using these apps: Tin-Lok Wong, Roni Ramirez, Mejgan Afshan, and Mariel Horner.

The collective has raised $15,380 since they began gathering donations in December, and redistributed those funds among 250 captives. On Sunday, over $3,000 was raised and about 50 A-Numbers were collected. Around six bottles and a deodorant were thrown over the fence that day, containing anywhere from one to nine A-Numbers.

Captives and organizers have set up a system: If a detainee uses their phone call to provide organizers with the A-Numbers of all of the individuals in their pods (the group they are detained with), that phone call will be reimbursed.

Inside of the detention center Wong says, captives work for $1 a day– a single 15-minute phone call is $5, according to Wong.

“I'm here at otay mesa detention center since December 03,2024, after long time I called my family because of you thank you so much for your kind support in my critical situations,” wrote a person held captive in a text to the vigil organizers.

“After almost 1 year I talked with my family and relatives, I buy some commissary too.”

During the vigil, organizers use megaphones to communicate with captives. Captives yell back, although it is often difficult to hear over the distance. They yell names, A-numbers, and request songs this way too.

To be heard better, captives began yelling through a drainage opening at the bottom of the wall. They must be laying down on the floor to access it, says Wong. Organizers began using a listening device to better hear their responses.

A woman's voice can be faintly heard emanating from behind the detention center wall. She says her name. We will not be including it in this piece due to safety concerns.

“Ya tengo tu numero!” Gonzalez yells into a megaphone.

The communication is imperfect—“Rusia” yells one of the detainees in Spanish—organizers scramble to see if anyone in attendance speaks Russian. Then, they realize that the detainee is saying it in Spanish so there is not a need for a Russian translator. What the detainee is trying to communicate with them is that the person whose A-number they are about to share is Russian.

Captives inside the facility come from many different countries and some don’t speak English. The collective has members that speak Arabic, Farsi, Mandarin, Cantonese, Russian, Swahili, Spanish, Togalog, Vietnamese, French, Creole, Mixtec, and Napoli. When detainees don’t speak English but are trying to communicate across the wall, they step in. That’s just a sampling of the languages that they have translators for.

Organizers have a playlist they play on speakers during the vigil. New songs are added every week based on what the detainees have requested. Artists on the playlist range from Grupo Firme to Taylor Swift to KNHO, a Russian rock band. Wong says one of the first things they asked captives when they began communicating over the wall was if they wanted to hear music, which captives do not have access to inside, she says.

“We're like, ‘Is there anything you want to hear?’ and they started yelling songs over,” Wong tells L.A. TACO. “And then we're like, ‘Oh, you know what? Maybe we could get their A numbers.’ So we could put money on their books and like, so some of the visitors would come out and they would come and talk to us.”

“It’s non-punitive,” she continues. “I don’t understand why they can’t have music, that’s nuts to me.”

The majority of immigration detentions in San Diego have been of people with no criminal record, according to reporting by KPBS.

Arturo Gonzalez, a San Diego community patroller and frequent vigil attendee, tells L.A. TACO Yulissa Callejas Garcia, who was kidnapped by federal immigration agents from Oxnard and held captive at the detention facility, yelled over the fence to organizers.

Her family was not aware of her whereabouts and they had no idea where she was at the time. Yelling her name to organizers allowed her to be connected with her family.

“We were just putting pieces together, like, ‘Okay, we have a number and now we'll see what we can do with this number.’ Like we didn't even really know what to do with the numbers when we had them yet until we started to learn more,” Gonzalez says.

About five or six weeks into the vigil, they noticed that something had been thrown over the fence. The organizers ran over to where the object had landed, and saw that there were A-numbers written on it. Then, the next week came the lotion bottles. Then, a shampoo bottle with more A-numbers. Some of the objects thrown over would get stuck in the fence.

“One number [recieved through] yelling and screaming could get us ten numbers through the portal,” says Gonzalez, allowing for text message communication with the captives through the detention center app.

In December, Gonzalez led the “Occupy Otay” action. He spent two nights sleeping outside of the detention center. A few people joined him, keeping him company, bringing coffee and snacks.

“At nighttime, we hear people playing handball because they were out there late at night. They let them outside at night. And so we were able to experience something that you wouldn’t otherwise experience unless you were there late at night. And it’s really silent, it’s really cold,” says Gonzalez, who plans to organize more overnight stays when warmer weather arrives.

Wong tells L.A. TACO that detainees face retaliation within the detention center for communicating with the organizers.

“We hear you, but the administration punishes all the pod by closing the yard for trying to communicate with you usually the[y] take away the access to the phone, tablet, family visit and commissary from 15 to 30 days,” reads a text message sent from one of the detainees inside of the facility, sent by an organizer and reviewed by L.A. TACO.

In November, when they began their weekly action, the detention facility temporarily stopped visitors from entering the facility due to the vigil. In response, Wong went inside to talk to the detention center warden and the sheriff who was there. She asked if it was a problem for organizers to be there on public property. They said it was not a problem, and she asked them to let the visitors in.

She told the warden about an action they were planning in an effort to ensure that visitations would not be shut down. She gave the warden her cell phone number, and told him to text her if they had any problems with their demonstration.

On another occasion, Wong went inside the detention center to ask the warden if there was an easier way to transfer the funds they raised directly to captives. The warden said he would look into it. Fourteen weeks later, Wong says nothing has come from it.

Wong also says that the conditions inside are so desperate that they are willing to face retaliation to communicate with folks on the outside, something she deeply empathizes with.

In June, Wong was disappeared into the basement of a facility in San Ysidro for "processing" and placed into solitary confinement for 21 hours by federal immigration agents. She was taken while she was at the Linda Vista Apartments during federal immigration agent activity. She was not found sooner because there is nowhere to register U.S. Citizens in the facilities system, she says.

She says that federal immigration agents told her that they could do anything they wanted to her and that she was no longer in the United States. She also says the agents mentioned the death of a man in detention, then said, “Yeah, you know, crazy things happen.”

She is currently fighting a felony charge for assault on a federal officer after she unmasked a federal immigration during the incident.

Attendees of the vigil fly kites, blow bubbles, and draw on the sidewalk with chalk. Dogs and children mingle.

Wong, who is a Pre-School teacher, says that, from the onset of the action, they intended for the space to be safe and inviting for all ages and species. Faith leaders across denominations pray over the captives and offer words of encouragement.

The rest of the note received by vigil organizers on Sunday reads:

“There is no internet. My lawyer was not given my phone calls. We are constantly sick. Our judge changed the final court decision. The judges are very busy. They have postponed our court three times. After 190+ days, we still don’t have a final court decision.

We were tortured in our own country and now being held indefinitely in a prison and unable to prepare for our trial.

They won’t give us a schedule. We are sitting indefinitely. They won’t give us a lawyer. There is no legal counsel. We can’t read or write to influence them. The law does not understand language barriers.

The lawyers don’t respond to positive feedback in our deportation interview or the due process interview. The library only has English-language books. There are no sports.

We are not sure of the final outcome and are now being held in prison indefinitely without the opportunity to properly prepare for trial.

We are in dire straits and are pleading for help. Many people here have been sitting for 12, 14, 16, 18 months without a final court decision.”

Wong says they have been urging their members of Congress to enter the detention facility unannounced. She says that the note they received on Sunday was shared with U.S. Representative Juan Vargas. Trump administration officials have, in many instances, stopped congressional representatives from conducting oversight at these facilities, according to KPBS.

Representative Juan Vargas’s office said that the Congressman is aware of the allegations and will be conducting an oversight visit at Otay Mesa Detention Center.

County Supervisor Tara Lawson-Remer called for local officials to be given access to the detention facility, according to reporting by KPBS.

In July, the detention center was over its contractual capacity of 1,358 detainees, according to KPBS reporting. Lawyers they spoke with said their clients faced rooms with not enough beds, and were getting sick due to medical neglect and unsanitary conditions.

The vigil is held outside of the Otay Mesa Detention Center every Sunday from 1:30 p.m. to 4 p.m.

“To us, it's a concentration camp,” Gonzalez tells L.A. TACO. “It's an unjust facility. It's something that shouldn't exist.”

L.A. TACO reached out to CoreCivic, U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement , and Congressmembers Sarah Jacobs and Juan Vargas. We will update this story if we hear back.

UPDATE: Representative Vargas was denied access to the Otay Mesa Detention Center today. The warden told Vargas he was given a directive by U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement to deny access. The warden provided a letter from the Department of Homeland Security to Vargas.

The Racial Justice Coalition of San Diego is also a part of the Otay Mesa Detention Collective.